In this QNL, I assess rulings issued by Dutch legal institutions published on www.rechtspraak.nl during the last week of October 2015 using Python‘s natural language processing, data analysis and machine learning packages.

Number of cases by institution

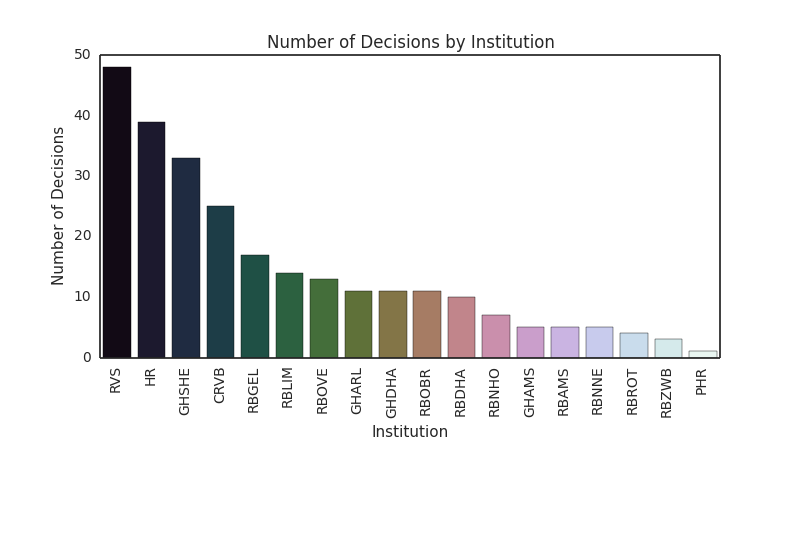

Between October 26 to November 1, 2015, a total of 262 new court rulings were published (list), according to a request via the site’s API. The graph below shows the number of rulings per issuing instution.

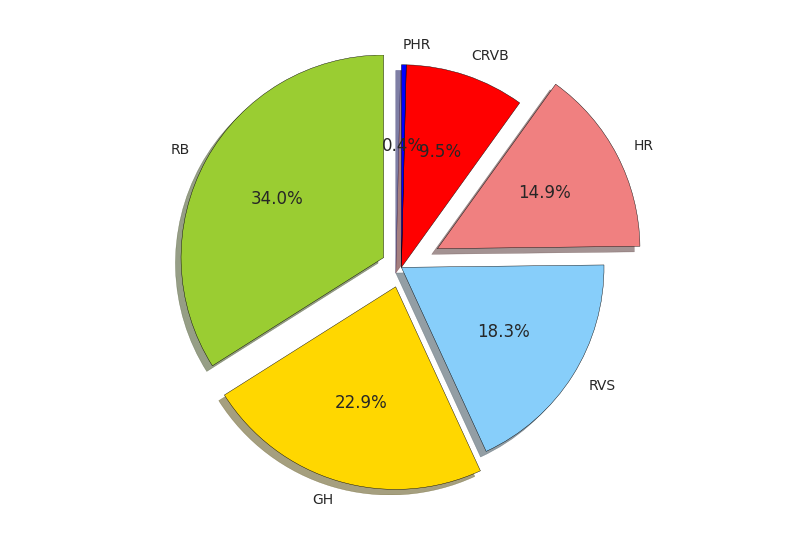

The Council of State (RVS, Raad van State) issued the highest number of rulings (48), followed by the Supreme Court (39) and the Appellate Court of ‘s-Hertogenbosch (33). Summing by institutional level, a predictable pattern emerges. The courts of first instance issued the greatest number of decisions, followed by the appellate courts. The relative shares are shown below.

Although the Attorney General (‘procureur generaal’, art. 111 Wet op de rechterlijke organisatie) technically is not an independent judicial body and only issues writes advisory opinions, I include those opinions in the analysis. The advisory opinions of the Attorney General are authoritative in Dutch legal circles, as they often provide guidance for judges at the trial and appellate levels.

It should be noted that the most rulings issued by the Supreme Court (22 of 39) are “article 81 RO” rulings. In such a ruling, the Supreme Court decides that (1) neither the appellant’s complaints are sufficient to warrant reversal of the appellate court’s decision, (2) nor is publication of the Supreme Court’s decision required for the sake of legal uniformity or development of the law. In addition, in a smaller number of rulings (4 of 39), the Supreme Court dismissed the complaint for inadmissibility.

Number of institutions by area of law

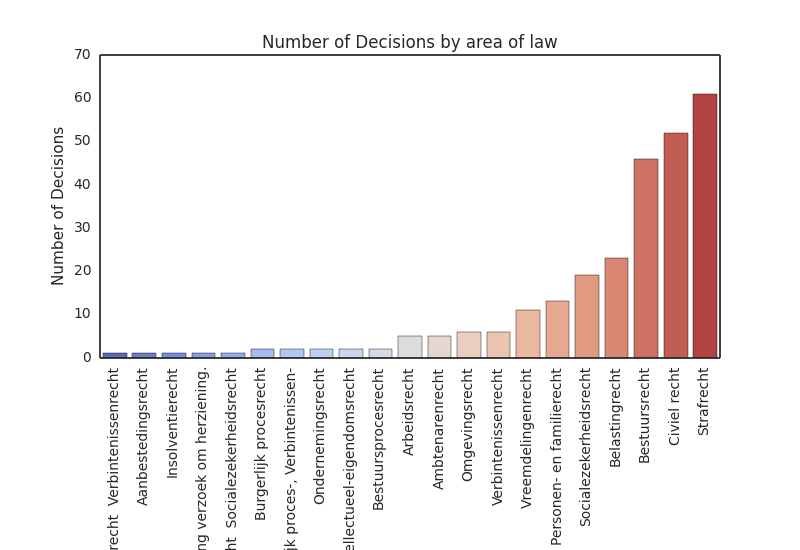

This week, most rulings involved criminal law (61), followed by civil law (52) and administrative law (46). As discussed in a prior post, most cases tend to fall in these general areas of law, rather than more narrowly defined areas such as employment law (5) and business law (2). However, any 1L (first year law student) knows that it’s not the category that matters, but the legal principle discussed (see more below). A graph with the legal categories and frequency counts for this week is posted below.

Throughput time

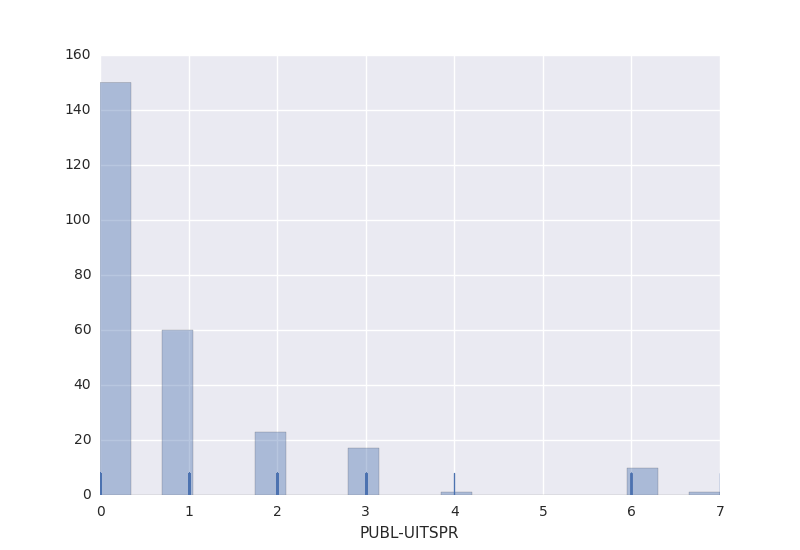

How much time elapses between the decision date and the publication date?

Most cases are published on the date of the actual decision (150 of 262 or 58%), but in 38% (100 of 262) of the cases it takes 1-3 days to publish the decision. If it took 1 day, it was most likely the Appellate Court of ‘s-Hertogenbosch (GHSHE, 22) or the Central Council of Appeal (CRVB, 13). A salient fact is that those courts handled a disproportionately large number of family law (GHSHE) and social security law (CRVB) cases. It’s merely salient: I did not compute any correlations between area of law and throughput time, which would be a poor measure for several reasons.

N-gram analysis

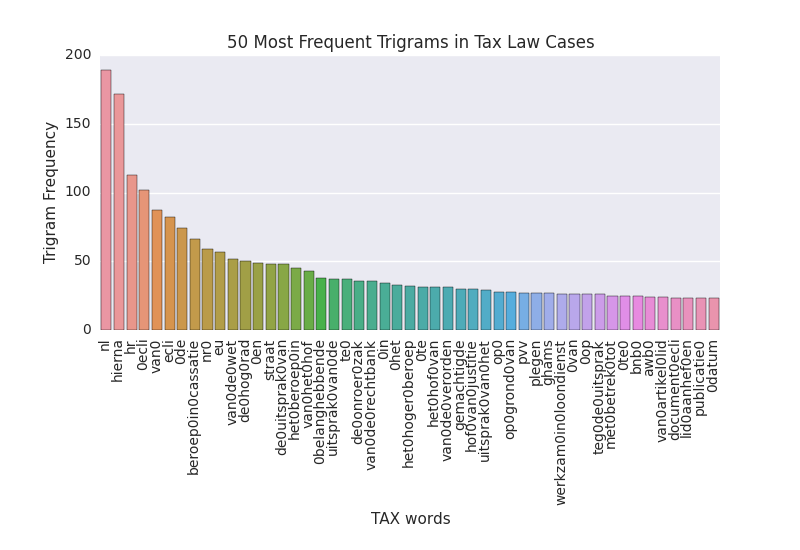

The analysis of n-grams are a fundamental element of any data analysis involving text. Roughly speaking, n-grams are sets of words that occur in the text, consisting of one (unigram), two (bigram) or three (trigram) words. In an n-gram analysis, the documents of the corpus are converted to a matrix with a vector for each n-gram, which facilitates the application of quantitative clustering or classification techniques (in combination with NLP tools such as a lemmatizer). The matrix can contain interesting information, such as the Most Important N-Gram (MING). With the MING approach, textual differences and similarities become apparent. Prior to using MING to classify texts (future posts), let’s contrast the most frequent unigrams in all civil law (52) and tax law (23) cases (top 50 unigrams, bigrams and trigrams).

What Does The Trigram Analysis Reveal? The main advantage of n-gram analysis is its simplicity. The trigram analysis shows that most tax cases are Supreme Court cases (“beroep in cassatie”, “de hog rad”) and refer more often to precedents (“ecli”), while civil law cases contain more statements concerning the parties (“appellant”, “geïntimeerde”). The unigram analysis shows that demonstrative pronouns (“die”), connectors (“of”), plaintiff (“appellant”), appellate court (“hof”) and lawyer (“advocaat”) occur frequently throughout the corpus.

The tables clearly illustrate the main drawbacks of independent n-gram analyses. The first issue concerns “non-informative” words. Generally, courts use some nouns (e.g. “plaintiff”, “Court”) and pronouns (“that”, “he”) more often than words that are “informative” because they are only used in a particular subset of cases. For example, the nouns “bankruptcy” or “agreement” are less frequently used in all texts, but may occur more often in a particular subset of the corpus. The second issue concerns synonyms and pronouns. A court may switch between the words “shareholder”, “he” and “company” while referring to a parent corporation in a corporate group. The third and most important drawback is the loss of context. Even in the highly unlikely case that courts use only informative words and are consistent in their use of words, n-gram analyses ignore the textual context in which these words appear. The analyst only knows whether the court used the word(s), not how they were used. Yet, one of the most important characteristics of legal rules is that they establish legal relations between legal concepts.

In upcoming posts, I address these issues by adding new layers of legal analytics to the QNL. Feel free to post comments or send me a message!